John Santos: Drums Are the Voices of Our Ancestors

By Susan Frances

Unknowingly, one of the first instruments children begin to play is the drums whether it’s banging on their parent’s pots and pans or tapping their feet against the floor to a rhythm they hear in their heads. Rhythm is an essential ingredient to making music, and drummer John Santos not only believes it but asserts that the drums, in all of its various rhythmic patterns, tell people about history from bachata to tango. The drums link each individual to one another as the first instrument each person exercises to express themselves. Discovering past rhythmic patterns, enhancing them and adding to the lexicon of music makes the drums the voices of our ancestors.

Unknowingly, one of the first instruments children begin to play is the drums whether it’s banging on their parent’s pots and pans or tapping their feet against the floor to a rhythm they hear in their heads. Rhythm is an essential ingredient to making music, and drummer John Santos not only believes it but asserts that the drums, in all of its various rhythmic patterns, tell people about history from bachata to tango. The drums link each individual to one another as the first instrument each person exercises to express themselves. Discovering past rhythmic patterns, enhancing them and adding to the lexicon of music makes the drums the voices of our ancestors.

He professes, “The drums are indispensable and absolutely crucial to our history for a myriad of reasons.”

“They are the heartbeat and foundation of our music,” he declares. “They impel us to dance. They are the voices of our ancestors and the links between yesterday, today and tomorrow. They are the unifiers and communicators at the center of our respective communities. They are the documentation of our history in our own voices. They speak tongues, codes, rituals, and prayers. They are resistance.”

He argues, “Despite the considerable, centuries-long, concerted efforts to colonize and destroy the African drum in all its cultural manifestations and representations, it rose like a phoenix from the ashes to become once again, the center of our oppressed communities. As such, they are not only essential to understanding the history of our music, they are essential to understanding our history.”

He summarizes how he discovered the drums, “Seeing and hearing the Puerto Rican percussionists playing Cuban instruments (tumbadoras, bongos, timbales) in my grandfather’s band was a big inspiration.” He remembers, “I subsequently joined that band in 1967. At the same time, my older brothers and cousins began talking about their schoolmate who was combining the electric guitar that we all loved with those percussion instruments that our grandfather’s band used. It was Carlos Santana before his first record came out [in] 1968, and the burgeoning Latin Rock scene that he brought to the attention of the world made those percussive instruments that much more hip.”

“Also at the same time,” he recalls, “retired Cuban boxing champ Orlando Zulueta moved in across the street and gave me a copy of his friend Mongo Santamaria’s classic late ’50s Afro-Cuban percussion album Yambú. Among many other giants it featured the great Francisco Aguabella, who would become a huge inspiration and teacher for me. I was done at that point – permanently indoctrinated by enamored with Afro-Latin percussion.”

friend Mongo Santamaria’s classic late ’50s Afro-Cuban percussion album Yambú. Among many other giants it featured the great Francisco Aguabella, who would become a huge inspiration and teacher for me. I was done at that point – permanently indoctrinated by enamored with Afro-Latin percussion.”

Growing up in San Francisco, he was influenced by the Latin music around him, transitioning from playing for his family to performing professionally. He recounts, “That happened while I was in my grandfather, Julio Rivera’s band from about 1967 to 1972. We played always at my grandma Lisa’s house at 1054 Hampshire Street in the heart of San Francisco’s Mission District and other homes, but also at small clubs, cultural centers and rented halls throughout the Bay Area’s extended Puerto Rican community.”

“It was always a thrill to play with the elders,” he ruminates, “eat the mouth-watering food, get so much love and respect from everyone young and old and be privy to some of the conversations of the musicians who were always so experienced, well-travelled, bilingual, and full of captivating stories. I recognized and was excited at a very young age about the golden opportunity to learn so much in that setting – about rhythm, about music, about language, about dancing, and perhaps most importantly, about identity – MY identity and that of my family. The music speaks of who we are in the most unique, beautiful and expressive way.”

A great portion of Santos’ identity is influenced by “the Puerto Rican and Cape Verdean traditions,” which he finds pleasure in revealing to the public. “In both cases, it was typical criollo food, music, dance and language (Spanish and Portuguese) every weekend as the soundtrack and ambience of my childhood. We most certainly continue these traditions although not quite as often and now of course with the pandemic, it’s all on hold.”

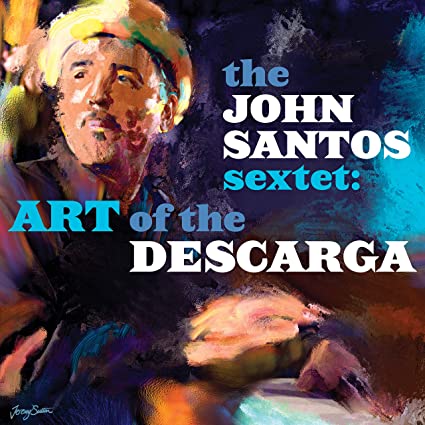

The history of Latin jazz is evident in Santos’ music whether its influences are shown in the works of his large orchestra under the moniker Machete Ensemble, or in his latest project titled the John Santos Sextet. His sextet’s latest release Art of the Descarga demonstrates the enthusiasm and authenticity of making music by means of improvised jam sessions or descarga as it’s called in the Spanish language. The musicians implement Cuban music themes during the session. Descarga is a style of music that is believed to have been developed in Havana, Cuba during the 1950’s. Santos brings this style of making music into the 21st century.

The history of Latin jazz is evident in Santos’ music whether its influences are shown in the works of his large orchestra under the moniker Machete Ensemble, or in his latest project titled the John Santos Sextet. His sextet’s latest release Art of the Descarga demonstrates the enthusiasm and authenticity of making music by means of improvised jam sessions or descarga as it’s called in the Spanish language. The musicians implement Cuban music themes during the session. Descarga is a style of music that is believed to have been developed in Havana, Cuba during the 1950’s. Santos brings this style of making music into the 21st century.

Joining Santos on the recording, he lists in order are: “Melecio Magdaluyo on saxophones, John Calloway on flute [and] piano, Marco Díaz on piano [and] trumpet, Saúl Sierra on bass, David Flores on drums,” and Santos on percussion and coro.

Santos recollects how he met each of his bandmates. “Melecio and I met when we played together in the San Francisco-based salsa band Sabor and in the Pete Escovedo Orchestra [druring the] early to mid-80s.”

He proceeds, “John Calloway and I met in Dolores Park in San Francisco mid-70s. Our 45-year collaboration began in 1976 when I directed San Francisco’s first charanga, Típica Cienfuegos. He was 15 or 16 and somewhat of a prodigy playing trombone, flute, percussion and writing arrangements.”

“Marco Díaz and I started playing in Calloway’s class at San Francisoc State and subsequently with various local salsa bands. When I invited him to join the group around 2004 or so, I didn’t even know that he played trumpet! That has been quite a blessing.”

“Saul Sierra and I met on a fun gig we did together with percussionist/bandleader Johnny Blas in 1999. I recommended him for the gig based on a reference from a friend back east who told me that he had just moved to the Bay Area. I then invited him to join the Quartet with the legendary Orestes Vilató, Marco and me.”

“Saul Sierra and I met on a fun gig we did together with percussionist/bandleader Johnny Blas in 1999. I recommended him for the gig based on a reference from a friend back east who told me that he had just moved to the Bay Area. I then invited him to join the Quartet with the legendary Orestes Vilató, Marco and me.”

“David Flores and I started playing with the local group O-Maya in the ’90s and he impressed me with his versatility and musical maturity being so young. When Orestes stepped down from the Quintet we had at the time, David was my first choice to step in and we’ve been playing a lot now in various settings since about 2008.”

He notes, “Although he is not on these recordings, Charlie Gurke has handled the sax duties for the last two years.”

Praising each of the musicians who joined him as “Extremely talented and wonderful human beings, all of them!” He specifies how Art of the Descarga was made possible, “I received a generous commission from the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival in San Francisco in 2014.”

“I challenged each member of the Sextet,” he imparts, “to contribute one original composition inspired in form and/or concept by the Cuban Descargas of the pioneers: virtuoso bassist Israel López (el gran Cachao), virtuoso pianist Bebo Valdés (father of Chucho), virtuoso pianist Pedro Justíz (Peruchín), master arranger Chico O’Farrill (father of Arturo), Niño Rivera (master tresero and arranger) and master pianist Julio Gutierrez. Being that the Sextet is made up of such incredible musicians and writers, it was not a problem nor a worry to tackle such a wide open and wide array of adventurous elements.”

“Aside from the canon recorded by the above-mentioned maestros during the ’50s,” he cites as the inspiration for the music on Art of the Descarga, “we infused some musical elements not commonly associated with the Descarga genre such as the changüí, son Jarocho, odd meter, batá and Arará. We also were inspired by the various neighborhoods in which we grew up.”

Each element in the Latin music lingo that he mentions is a style of rhythm, which he proclaims, “Rhythm is magnetic, it is what pulled me in. I feel like the drums chose me! I heard an awesome variety of music in the super rich musical environment of my San Francisco based family and community – Cape Verdean, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Brazilian, funk, soul, Motown, jazz, blues, rock, Latin rock, etc. ALL of it was and is rhythm-based. Even the Boys Club marching band for, which I played clarinet for three years in the mid-60s, had seductive rhythms being played by the percussionists and it really caught my attention.”

Prior to his present sextet, Santos made a considerable leap into the world market with his orchestra the Machete Ensemble. What beckoned him to create the outfit, he remarks is, “The desire to stretch out more as composers, arrangers, and soloists and depart a little more from the dance traditions that are at our roots. Also, a decade earlier, I had fallen in love with one of the greatest groups to ever rise from the San Francisco Bay Area – Azteca, led by Coke and Pete Escovedo. I still had that in my head and wanted to have a top notch horn section with a killer rhythm section à la Azteca. The previous groups I led, Orquesta Típica Cienfuegos (1976-1980) and Orquesta Batachanga (1981-1985), were charangas (violin and flute led ensembles with minimal horns).”

“We began to attract attention in the jazz world,” he observes, “playing Jazz festivals and recording regularly. We shifted our focus to playing much more original music, and last but not least, we collaborated from the beginning in the recording studio and onstage with major players, mentors and icons such as Armando Peraza, Cachao, Chocolate Armenteros, Carlos Santana, Joe Henderson, Steve Turre, Orestes Vilató, Jerry Medina, Maria Márquez, Destani Wolf, Andy Gonzalez, Jerry Gonzalez, Anthony Carrillo, Changuito, Paoli Mejias, Pedrito Martinez, Ernesto Oviedo, Rico Pabon, and countless others. We recorded nine CD’s in that time, mostly on my Machete Records label. One was Grammy nominated SF Bay. We also performed throughout California as well as in New York, Chicago, Havana, Philadelphia, and Boston among many other places.”

His move from leading a large ensemble to helming a sextet, he enlightens, “To be truthful, the downsizing was strictly for economic reasons. I had it in my mind and heart that the Machete ensemble would never end. It was a large group, particularly for the first ten years or so, but the decent paying work was gradually drying up. We tried to persevere, but berzerk capitalism such as ours makes it extremely difficult to survive as an artist if you are not consistently putting out what the industry deems popular and sellable. We eeked it out for 21 years, miraculously. It became impossible to maintain a large ensemble, so the downsizing happened.”

“However,” he regards, “on all the subsequent recordings, whether under the name John Santos Quintet, or Sextet, we always averaged around 30 folks with all the guests included. So in that way, we’ve kept the Machete spirit intact. But playing in the smaller groups has also been fun, eye-opening and a great learning experience for all of us, as the responsibility is intensified in the smaller groups – you simply have to cover more ground, play more solos, hold it down more completely for the other soloists, and deal with that always ominous mystery of more space to respect and from which to create. There is also more room for spontaneity in the smaller formats.”

He finds Latin jazz to be the music, “Definitely of the Americas” but “Most certainly” can be a part of the world music genre, and “Without a doubt” musicians outside of Latin America can play Latin jazz. Still, cannot imagine anyone else possessing the romantic flare and charisma of Latin singer Julio Iglesias except Julio Iglesias.

Like the music of Julio Igliesias, Latin jazz does open itself up to the world in Santos’ opinion as he attests “Affirmative,” to the question.

“Just like jazz, Latin jazz is a chameleon,” he discerns, “quite adaptable and even prone to fusions of different types. Our rhythms are ripe with pan-African influence and can mix very effectively with rhythms and forms from every corner of the world. Diz (Dizzy Gillespie) was a visionary in this respect, from his groundbreaking collaboration with Chano Pozo as architects of Cubop in 1947/48, to his last big project, the United Nations Orchestra. He walked the walk. I am so honored to have worked with him in the early ’90s with the Bebop and Beyond project of Bay Area sax icon Mel Martin.”

with pan-African influence and can mix very effectively with rhythms and forms from every corner of the world. Diz (Dizzy Gillespie) was a visionary in this respect, from his groundbreaking collaboration with Chano Pozo as architects of Cubop in 1947/48, to his last big project, the United Nations Orchestra. He walked the walk. I am so honored to have worked with him in the early ’90s with the Bebop and Beyond project of Bay Area sax icon Mel Martin.”

When comparing the experience of performing live to recording in a studio, Santos offers they are, “Entirely different. Both are exciting,” he concedes, “and expand one’s vision and understanding. But playing for an appreciative audience is what it is about. It is a communal ritual. A spirit lifter. An informer, strictly in the positive sense. A reminder that life is short, we have much more in common than what separates us, and we must absolutely take time to smell the roses. The live music experience creates empathy, unity, and love and inspires us all to be better in every way we can. When it’s just us, it’s like singing in the shower – might be great, might suck – who knows? Who cares? But the audience lifts the vibe, exponentially increases the collective call to spirit and pushes the artists to new heights. Everyone leaves inspired, hopefully. The more we learn, the better we become at understanding and channeling the profound, magical aspects of music.”

Another means of learning his trade and connecting to people has been his experiences as an educator. Teaching music and playing music, he views, “I feel that with Latin Jazz in particular, the two things go hand in hand. They depend on and inform each other. There is a lot of misinformation that needs correcting. They are bottomless wells and as long as one wishes to continue to learn, there is so much more to learn. We’ve been left marvelous and gorgeous artistic legacies by creative souls over the centuries. To ignore or brush off that part of our history and identity is to seriously shoot yourself in the foot as a practitioner, student, teacher, composer, arranger, presenter, supporter and even fan of this musical gift.”

“I’ve always felt,” he considers, “that in a classroom or educational situation of any kind, the one who learns the most is the teacher. Being an effective educator requires prep, study, practice, and humility. It is an ongoing attempt to be more natural, more effectively communicative, more confident, more knowledgeable, better able to transmit on physical, theoretical and spiritual levels. I don’t see how it is possible to go very far in this field if you have not studied and do not understand the history of colonialism and oppression and the social conditions which gave birth to this music. Like trying to play jazz while never learning anything about the blues. Without proper education and context, the most base, most commercial, most shallow aspects of consumerism swallow up the music and erase the precious legacies that were so hard-earned.”

Adding to Santos’ own legacy, the city of San Francisco selected November 12th to be John Santos Day, first celebrated in 2006. He shares how the day was chosen, “I got a call one day from the Mayor’s office. That’s all I know. Some kind folks must’ve recommended my name to them.”

He touts it is, “A great honor to say the least,” to have a day that celebrates him though he confesses, “To be honest, I don’t” celebrate the day. “My birthday is November 1st. If I tried to celebrate myself again 11 days after my birthday every year, my family wouldn’t let me get away with it! 😁 So I leave it alone.”

Beyond shaping his own legacy in Latin jazz, he expresses other goals on his wishlist, which he adduces, “I’d love to facilitate and see my kids (12 and 15) and my wife, the brilliant writer, Aida Salazar, continue to thrive and be healthy, happy, creative, and successful. I’d also love to continue playing, writing, performing, and teaching as I’ve done the past half a century. And last but not least, I’d love to achieve optimum health in my senior years. I really miss playing for audiences. It’s been 5 months and will likely be a lot longer. I hope it is not a thing of the past despite the ignorance and arrogance emanating from so-called leadership.”

When the drums stop beating so too does the rhythm of its people. History and musical influences are told and passed on from generation to generation through the rhythmic patterns of the drums. John Santos isn’t ready for it to all end now. The drums are the voices of our ancestors from Santos’ perspective. They are woven into us, and we carry the rhythms with us, passing them along to new generations who add their own imprint to the landscape.

About Susan Frances:

Born in Brooklyn, New York and raised in eastern Long Island, I always enjoyed writing and made several contributions to my high school literary magazine, The Lion’s Pen. Influenced by writers of epic novels including Colleen McCullough and James Clavell, I gravitated to creative writing. After graduating from New York University with a BA in Liberal Arts, I tried my hand at conventional jobs but always returned to creative writing. Since 1998, I have been a freelance writer and have over three thousand articles to various e-zines including: Jazz Times, Blogcritics, Yahoo Voices, Goodreads.com, Authors and Books (books.wiseto.com), TheReadingRoom.com, Amazon.com, Epinions.com, Fictiondb.com, LibraryThing.com, BTS emag, BarnesandNoble.com, RomanticHistoricalReviews.com, AReCafe.com, Hybrid Magazine, and BookDepository.com. In 2013 and 2014, I was a judge in the Orange Rose Writing Competition sponsored by the Orange County chapter of the Romance Writers of America located in Brea, California.

Born in Brooklyn, New York and raised in eastern Long Island, I always enjoyed writing and made several contributions to my high school literary magazine, The Lion’s Pen. Influenced by writers of epic novels including Colleen McCullough and James Clavell, I gravitated to creative writing. After graduating from New York University with a BA in Liberal Arts, I tried my hand at conventional jobs but always returned to creative writing. Since 1998, I have been a freelance writer and have over three thousand articles to various e-zines including: Jazz Times, Blogcritics, Yahoo Voices, Goodreads.com, Authors and Books (books.wiseto.com), TheReadingRoom.com, Amazon.com, Epinions.com, Fictiondb.com, LibraryThing.com, BTS emag, BarnesandNoble.com, RomanticHistoricalReviews.com, AReCafe.com, Hybrid Magazine, and BookDepository.com. In 2013 and 2014, I was a judge in the Orange Rose Writing Competition sponsored by the Orange County chapter of the Romance Writers of America located in Brea, California.

No Comments